On this day in 1916, a young swan was picked up "exhausted" and identified as a Tundra Swan (then Whistling Swan) at Elizabeth in Union County. This observation was included in a list of "unusual visitors" by Charles Urner that was published in the Auk in 1921. One issue later, there was a sequel. The swan (published as a Tundra Swan either through misidentification or typographical error: both are blamed) turned out to be a Mute Swan, which was at that time an introduced species with a very limited distribution in the New York City area. W. De Witt Miller at the American Museum of Natural History made the correct identification after seeing the bird. In 1932, Urner published a further account of the species' spread in NJ; at that point he said it was "completely naturalized...a number of pairs breed in a wild state in suitable ponds along the coast from the vicinity of Asbury Park to Bayhead" (Urner 1932). When Witmer Stone wrote Bird Studies at Old Cape May, he quoted Urner and noted that Mute Swan was not yet known to reach Cape May (Stone 1965). By the time Walsh et al. was published in 1999, Mute Swan was breeding across the state (including Cape May), mostly in the north, though the distribution was somewhat scattered. Coastal ponds remain excellent places to see Mute Swans; in spring, large numbers can be seen in various locations.

Urner, Charles A. 1932. Mute Swan in New Jersey. Auk 49:213. PDF here

Urner, Charles A. 1921. Unusual visitors at Elizabeth, N. J. Auk 38:120-121. PDF here

Urner, Charles A. 1921. Whistling Swan: A correction. Auk 38:273. PDF here

A calendar of noteworthy occurrences in New Jersey birding history, such as first state records. Also ruminations on documentation, sources, and historical matters, plus the occasional off-topic post or moth photo.

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

Buller's Shearwater

On this day in 1984, a Buller's Shearwater was found on a pelagic trip off the Jersey coast. The bird was about 31 miles ESE of Barnegat Light, and remains a unique record. This species breeds on islands near New Zealand and the NJ record is the single North Atlantic record of the species. See Angus Wilson's Ocean Wanderers site for more info about Buller's Shearwater and its usual distribution.

David Sibley was the one who identified the shearwater, according to the account in Records of New Jersey Birds. I recently heard someone who was there at the time say that it was one of only two times he ever heard Sibley shout (the other was for a Mississippi Kite, which just shows how much times have changed).

Dunne, Peter. 1985. 1984 Fall Field Notes, Region 5. Records of New Jersey Birds 11:18-22.

David Sibley was the one who identified the shearwater, according to the account in Records of New Jersey Birds. I recently heard someone who was there at the time say that it was one of only two times he ever heard Sibley shout (the other was for a Mississippi Kite, which just shows how much times have changed).

Dunne, Peter. 1985. 1984 Fall Field Notes, Region 5. Records of New Jersey Birds 11:18-22.

Saturday, October 24, 2009

Happy Birthday, Brig!

On this day in 1939, Brigantine NWR (later renamed Edwin B. Forsythe NWR) was unleashed upon an unsuspecting public. Although the original intent was to serve as refuge for waterfowl (i.e., game birds), it eventually became a magnet for birders because of its habit of attracting rarities in many bird groups (see below).

I first visited Brig in 1989, on one of my first birding trips. That was my introduction to coastal salt marshes, the day I learned how to use a checklist, and the day that the car's radiator overheated so that we had to limp homeward on Rt. 9 until we finally washed up at the Cranberry Bog (an opportune restaurant with a pay phone so that the driver's father could be summoned to the rescue). I got about 20 lifers that day, never mind the memories.

Then there was the World Series of Birding day when we were headed out along the south dike and the driver (same driver, different car) said, "Don't look behind you." Of course I did, only to see a wall of evil-looking clouds coming in from the west. The tempest blew through, with lightning strikes in the impoundments. Even in the dark of the storm, we could see the white rumps of the White-rumped Sandpipers as they flushed when the lightning struck. Other shorebirds took the opportunity to bathe as the rain poured down. We didn't get most of the birds we had hoped to add at Brig that day, but the weather drama was unforgettable.

Then there have been all the rarities I chased and missed at Brig over the years, the few I chased and got, and, of course, the greenheads. And the seasonal blizzards of Snow Geese. And the peregrines. And the wind in the marsh grass. Etc., etc. I could go on and on. A long-term relationship like the one I have with Brig can't be reduced to a single blog post.

To conclude, here is an incomplete list of some good birds we can thank Brig for (drawn from the most recent edition of the NJBRC Accepted Records List; asterisks indicate first state records):

Black-bellied Whistling-Duck - 2000*

Fulvous Whistling-Duck - 2004

Greater White-fronted Goose - 1993, 1996

Ross's Goose - 1972*, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1993, 1996, 1997

"Black" Brant - 2001

Cinnamon Teal - 1974*

Garganey - 1997*

"Common" Teal - 1997

Eared Grebe - 1986, 2007

American White Pelican - 1996

Reddish Egret - 1998*

White Ibis - 1996, 1998, 2007

White-faced Ibis - 1981, 1983, 1986, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1999, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2007

Roseate Spoonbill - 2007

Swallow-tailed Kite - 1988

Gyrfalcon - 1941, 1971, 1972, 1975

Yellow Rail - 1971

Purple Gallinule - 1964, 1971, 1974, 1985, 1993, 1998

Sandhill Crane - 1998

Wilson's Plover - 1979, 1996, 1999, 2007

Black-necked Stilt - 1996

Spotted Redshank - 1978*, 1979, 1993

"Eurasian" Whimbrel - 2001

Long-billed Curlew - 2001

Black-tailed Godwit - 1971*

Bar-tailed Godwit - 1971

Red-necked Stint - 1999*

Little Stint - 1985*

Curlew Sandipiper - 2001, 2002, 2003, 2007

Sooty Tern - 1979

Pacific-slope/Cordilleran Flycatcher - 1981*

Say's Phoebe - 1960, 2003

Ash-throated Flycatcher - 2007

Gray Kingbird - 1993

Scissor-tailed Flycatcher - 1995

Fork-tailed Flycatcher - 1972, 1995, 1999

Cave Swallow - 1999, 2007

Northern Wheatear - 1970, 1974, 1983, 1995

Mountain Bluebird - 1982*

Bohemian Waxwing - 1999

Black-throated Gray Warbler - 1984

Townsend's Warbler - 2006

Western Tanager - 2005

Happy 70th birthday, Brig!

I first visited Brig in 1989, on one of my first birding trips. That was my introduction to coastal salt marshes, the day I learned how to use a checklist, and the day that the car's radiator overheated so that we had to limp homeward on Rt. 9 until we finally washed up at the Cranberry Bog (an opportune restaurant with a pay phone so that the driver's father could be summoned to the rescue). I got about 20 lifers that day, never mind the memories.

Then there was the World Series of Birding day when we were headed out along the south dike and the driver (same driver, different car) said, "Don't look behind you." Of course I did, only to see a wall of evil-looking clouds coming in from the west. The tempest blew through, with lightning strikes in the impoundments. Even in the dark of the storm, we could see the white rumps of the White-rumped Sandpipers as they flushed when the lightning struck. Other shorebirds took the opportunity to bathe as the rain poured down. We didn't get most of the birds we had hoped to add at Brig that day, but the weather drama was unforgettable.

Then there have been all the rarities I chased and missed at Brig over the years, the few I chased and got, and, of course, the greenheads. And the seasonal blizzards of Snow Geese. And the peregrines. And the wind in the marsh grass. Etc., etc. I could go on and on. A long-term relationship like the one I have with Brig can't be reduced to a single blog post.

To conclude, here is an incomplete list of some good birds we can thank Brig for (drawn from the most recent edition of the NJBRC Accepted Records List; asterisks indicate first state records):

Black-bellied Whistling-Duck - 2000*

Fulvous Whistling-Duck - 2004

Greater White-fronted Goose - 1993, 1996

Ross's Goose - 1972*, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1993, 1996, 1997

"Black" Brant - 2001

Cinnamon Teal - 1974*

Garganey - 1997*

"Common" Teal - 1997

Eared Grebe - 1986, 2007

American White Pelican - 1996

Reddish Egret - 1998*

White Ibis - 1996, 1998, 2007

White-faced Ibis - 1981, 1983, 1986, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1999, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2007

Roseate Spoonbill - 2007

Swallow-tailed Kite - 1988

Gyrfalcon - 1941, 1971, 1972, 1975

Yellow Rail - 1971

Purple Gallinule - 1964, 1971, 1974, 1985, 1993, 1998

Sandhill Crane - 1998

Wilson's Plover - 1979, 1996, 1999, 2007

Black-necked Stilt - 1996

Spotted Redshank - 1978*, 1979, 1993

"Eurasian" Whimbrel - 2001

Long-billed Curlew - 2001

Black-tailed Godwit - 1971*

Bar-tailed Godwit - 1971

Red-necked Stint - 1999*

Little Stint - 1985*

Curlew Sandipiper - 2001, 2002, 2003, 2007

Sooty Tern - 1979

Pacific-slope/Cordilleran Flycatcher - 1981*

Say's Phoebe - 1960, 2003

Ash-throated Flycatcher - 2007

Gray Kingbird - 1993

Scissor-tailed Flycatcher - 1995

Fork-tailed Flycatcher - 1972, 1995, 1999

Cave Swallow - 1999, 2007

Northern Wheatear - 1970, 1974, 1983, 1995

Mountain Bluebird - 1982*

Bohemian Waxwing - 1999

Black-throated Gray Warbler - 1984

Townsend's Warbler - 2006

Western Tanager - 2005

Happy 70th birthday, Brig!

Monday, October 19, 2009

Bird Documentation in the Digital Age: What Is a Bird Record?

"Whenever I think seriously about why I love notebooks I'm reminded of those cave walls covered in drawings of game by our Neolithic ancestors. Bison, deer and horses gallop across their subterranean galleries in exuberant patterns of charcoal and ochre....They are precious documents about our past, but also about our present condition, since their unconscious beauty finds its echo - if not a direct lineal descendant - in the birder's notebook." (Cocker 2001)

In the beginning, there was a bird.

Some time afterward, there was a human being that wanted to tell other human beings about a bird. This would have been long before any form of written language was invented, so speech was the likely medium (though birds also appear in cave and rock art, of course). Since speech tends to be ephemeral unless it is written down or it persists in a carefully-maintained oral tradition, those earliest bird reports are lost to us today. This is unfortunate, since they would doubtlessly be very interesting.

An encounter between a bird and a human observer is a unique experience. A bird report is the result of that unique experience being translated into a form that allows it to be communicated to people that did not participate in the original experience. That translation is often made with the help of technology. The type of technology used in the translation process inevitably affects the final form of the report (for example, a written description of a bird and a photograph of a bird are very different from each other, even if they report the same individual bird). Technology may affect the circumstances of the observation as well.

The distinction between a bird report and a bird record is subtle but significant. A bird record is a bird report that has been examined and approved by a person or agency with the authority to designate what is accurate and what is not. Various entities claim this authority; the claims of ornithologists and bird records committees are widely accepted by the birding community and others, but any individual can claim a similar authority (whether that claim is honored by others is another matter entirely). To complicate matters further, different authorities may have different criteria for considering a report to be a record.

Both bird reports and records become part of the avian historical record, although a bird record has more status than a report. A basic criterion for a bird record is that there is sufficient information available for future reseachers to review the evidence for a claimed observation and draw their own conclusions. In other words, though current authorities do the best they can in terms of designating accuracy, there is an acknowledgement that future generations may make different designations. Future researchers may even look at observations currently considered to be reports and upgrade them to being records (or vice versa).

To boil it all down to the essentials, the process of turning a bird report into a bird record is the process of turning an anecdote into a data point.

What you just read (if you are still with me) is an idealized version of a stable situation. Technological and social change (which are often entwined with each other) tend to throw such ideals into chaos until a new status quo appears. We are currently living through one of these periods of technological and social change, but the next post in this series will look back at a previous shift: the transition from a shotgun to binoculars as the must-have tool for a bird student.

Cocker, Mark. 2001. Birders: Tales of a Tribe. Atlantic Monthly Press.

Previously in this series:

Introduction

In the beginning, there was a bird.

Some time afterward, there was a human being that wanted to tell other human beings about a bird. This would have been long before any form of written language was invented, so speech was the likely medium (though birds also appear in cave and rock art, of course). Since speech tends to be ephemeral unless it is written down or it persists in a carefully-maintained oral tradition, those earliest bird reports are lost to us today. This is unfortunate, since they would doubtlessly be very interesting.

An encounter between a bird and a human observer is a unique experience. A bird report is the result of that unique experience being translated into a form that allows it to be communicated to people that did not participate in the original experience. That translation is often made with the help of technology. The type of technology used in the translation process inevitably affects the final form of the report (for example, a written description of a bird and a photograph of a bird are very different from each other, even if they report the same individual bird). Technology may affect the circumstances of the observation as well.

The distinction between a bird report and a bird record is subtle but significant. A bird record is a bird report that has been examined and approved by a person or agency with the authority to designate what is accurate and what is not. Various entities claim this authority; the claims of ornithologists and bird records committees are widely accepted by the birding community and others, but any individual can claim a similar authority (whether that claim is honored by others is another matter entirely). To complicate matters further, different authorities may have different criteria for considering a report to be a record.

Both bird reports and records become part of the avian historical record, although a bird record has more status than a report. A basic criterion for a bird record is that there is sufficient information available for future reseachers to review the evidence for a claimed observation and draw their own conclusions. In other words, though current authorities do the best they can in terms of designating accuracy, there is an acknowledgement that future generations may make different designations. Future researchers may even look at observations currently considered to be reports and upgrade them to being records (or vice versa).

To boil it all down to the essentials, the process of turning a bird report into a bird record is the process of turning an anecdote into a data point.

What you just read (if you are still with me) is an idealized version of a stable situation. Technological and social change (which are often entwined with each other) tend to throw such ideals into chaos until a new status quo appears. We are currently living through one of these periods of technological and social change, but the next post in this series will look back at a previous shift: the transition from a shotgun to binoculars as the must-have tool for a bird student.

Cocker, Mark. 2001. Birders: Tales of a Tribe. Atlantic Monthly Press.

Previously in this series:

Introduction

Saturday, October 10, 2009

Bird Documentation in the Digital Age: Introduction

At the beginning of this year, two Ivory Gulls appeared in eastern Massachusetts. Since both birds stayed for a while, crowds of birders got to see them; not only local birders but twitchers from far away. I was among the twitchers, as two friends and I made a memorable day trip to Plymouth and saw the bird. By the time we went for the bird, many photos had been posted online to Flickr and other sites, and many of those photos were taken at invitingly close range. When we were there, however, the gull stayed out on the jetty and even farther out in Plymouth Harbor. We did get to see it, though, and it was a lifer for all of us.

Once I got home, I knew I should be a good birding citizen and submit a writeup on the bird to MARC, the Massachusetts Avian Records Committee. As usual, however, I didn't get to it as soon as I wanted and several weeks passed before I e-mailed a description taken from my field notes to the MARC Secretary. The reply I got startled me: I was informed that I was the only person who had submitted written details on the bird up to that point. Granted, with such wonderful photos so easily available, MARC's acceptance of the record was unlikely to hang on my details, but I would have assumed that somebody else, somewhere, would have written some sort of description (and perhaps someone has, in the long interim between my submission and the writing of this post).

The process of bird documentation has undergone a sea-change since I started birding. This begins a series of posts intended to examine this phenomenon in more detail: where we've been and where we're going, and some of the issues that have arisen as a result. Although documentation of rarities may seem like an uncommon situation to many birders, I see that kind of documentation as the tip of the iceberg that is really how we as birders record all birds that we observe.

Next: What, exactly, is a bird record?

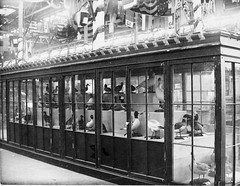

The photo that illustrates this post was taken by Jason Forbes in Plymouth on 24 January 2009 (the day I was there) and is under a Creative Commons license. Jason's blog is Brewster's Linnet and he also has a Flickr stream.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)