On this day in 1976, a Le Conte's Sparrow was found at Tuckerton in Ocean County by Richard Ryan, K. Richards, and Frank and Barb Haas; the bird stayed until 2 October and many others also saw it. This species, one of the skulking Ammodramus sparrows, has seen a marked upsurge in the Northeast in recent decades; at least some of this has to be due to the fact that there are more observers in the field, and more knowledge about identifying Le Conte's Sparrows. New York has a specimen record from 1897 near Ithaca, so the species is not a newcomer to the region (Levine 1998). It will always be a challenge for an observer to find a Le Conte's Sparrow, however, whether the birding technology of choice is optical equipment or a shotgun.

Of NJ's 24 records so far, 20 have come since 1990. Other Northeastern states show a similar temporal pattern. Although Cape May has seven Le Conte's records, Monmouth County has nine, helped in large part by the north end of Sandy Hook. The first state record was a tad early, as it turned out; about 50 percent of NJ Le Conte's records come from October. So get out your field guides and study up; both Grasshopper Sparrow and Sharp-tailed Seaside Sparrow bear a passing resemblance to Le Conte's Sparrow.

Levine, Emanuel. 1998. Bull's Birds of New York State. Comstock, Ithaca, NY.

A calendar of noteworthy occurrences in New Jersey birding history, such as first state records. Also ruminations on documentation, sources, and historical matters, plus the occasional off-topic post or moth photo.

Tuesday, September 26, 2006

Monday, September 25, 2006

Anhinga

On this day in 1971, an Anhinga was seen at Cape May by K. Berlin, B. Baumann and others. The bird was soaring with Broad-winged Hawks, an unusual sight in NJ but not so out of the ordinary in places like Hazel Bazemore Hawkwatch in Corpus Christi, Texas.

Many first state records set a pattern which is reinforced by later records of the species. Not so Anhinga. The first record was a fall bird, but it took until 2005 to get another fall record of the species. That makes two fall records out of 13 total Anhinga records, so far. An oddity is a dead Anhinga found 16 January 1989 in Whiting, Ocean County. The spring records range from 24 April to 27 June, with five in May.

Anhingas are notorious for being fly-over birds that can never be relocated. These fly-overs usually leave little time for observation, which raises the odds for misidentification. A fly-over bird usually can't be independently confirmed by other birders, either, which adds to the frustration. Some species have a reputation for being "one-day wonders" but Anhingas might be "five-minute wonders." Jersey birders who've done time in Florida might be particularly frustrated, since Anhingas are so cooperative down there.

Many first state records set a pattern which is reinforced by later records of the species. Not so Anhinga. The first record was a fall bird, but it took until 2005 to get another fall record of the species. That makes two fall records out of 13 total Anhinga records, so far. An oddity is a dead Anhinga found 16 January 1989 in Whiting, Ocean County. The spring records range from 24 April to 27 June, with five in May.

Anhingas are notorious for being fly-over birds that can never be relocated. These fly-overs usually leave little time for observation, which raises the odds for misidentification. A fly-over bird usually can't be independently confirmed by other birders, either, which adds to the frustration. Some species have a reputation for being "one-day wonders" but Anhingas might be "five-minute wonders." Jersey birders who've done time in Florida might be particularly frustrated, since Anhingas are so cooperative down there.

Labels:

"cape may county",

"cape may",

1971,

anhinga

Saturday, September 23, 2006

Black-throated Gray Warbler

On this day in 1956, W. Parker, Ed Bloor and Charles Rogers found a Black-throated Gray Warbler at Tuckerton in Ocean County.

September is the peak month in NJ and most nearby states for this dapper-looking Western stray. NJ has 19 records of the species at this writing, nine of which are September records. Two-thirds of these occur in the span between 20 September and the end of the month. Most of the rest of the state's records come from fall, going into December in two cases; there are a couple of "early" records for August as well. There are only two spring records. In other words, this species shows a temporal pattern typical of a Western vagrant, although its occurrence peaks earlier in the season than the many Western species that have made November a month to be reckoned with for rarity-chasers.

No fewer than four individuals have been banded at Island Beach State Park in Ocean County, while there are seven accepted records from Cape May (and Sibley 1997 lists two more reports) (Hanson 2002-2003). Although at first glance, the species shows up in the expected coastal vagrant traps, there are also six inland records scattered across the state from Franklin in Sussex County to Mickleton in Gloucester County. One real oddity is that the species has never been recorded at Sandy Hook, which would seem like an obvious site for it to turn up.

Black-throated Gray Warbler is not quite annual in NJ, but it is a regular rarity, so most birders will get a chance to chase one sooner rather than later.

Hanson, Jennifer W. 2002-2003. The Status of Black-throated Gray and Townsend's Warblers in New Jersey. Records of New Jersey Birds 28:24-78.

Sibley, David. 1997. The Birds of Cape May. New Jersey Audubon Society, Bernardsville, NJ. Second edition.

September is the peak month in NJ and most nearby states for this dapper-looking Western stray. NJ has 19 records of the species at this writing, nine of which are September records. Two-thirds of these occur in the span between 20 September and the end of the month. Most of the rest of the state's records come from fall, going into December in two cases; there are a couple of "early" records for August as well. There are only two spring records. In other words, this species shows a temporal pattern typical of a Western vagrant, although its occurrence peaks earlier in the season than the many Western species that have made November a month to be reckoned with for rarity-chasers.

No fewer than four individuals have been banded at Island Beach State Park in Ocean County, while there are seven accepted records from Cape May (and Sibley 1997 lists two more reports) (Hanson 2002-2003). Although at first glance, the species shows up in the expected coastal vagrant traps, there are also six inland records scattered across the state from Franklin in Sussex County to Mickleton in Gloucester County. One real oddity is that the species has never been recorded at Sandy Hook, which would seem like an obvious site for it to turn up.

Black-throated Gray Warbler is not quite annual in NJ, but it is a regular rarity, so most birders will get a chance to chase one sooner rather than later.

Hanson, Jennifer W. 2002-2003. The Status of Black-throated Gray and Townsend's Warblers in New Jersey. Records of New Jersey Birds 28:24-78.

Sibley, David. 1997. The Birds of Cape May. New Jersey Audubon Society, Bernardsville, NJ. Second edition.

Labels:

"ocean county",

1956,

tuckerton,

warbler

Friday, September 22, 2006

Cassin's Sparrow

On this day in 1961, a Cassin's Sparrow was netted and collected by Mabel Warburton at Island Beach State Park as part of Operation Recovery. The specimen ultimately went to the American Museum of Natural History in New York to have the identification confirmed. It was aged as an immature (Swinebroad 1966).

Cassin's Sparrow is a very rare vagrant in the East; there are a few records for the Midwest. One bird made it all the way to Seal Island, Nova Scotia in 1974; that was a spring bird (Tufts 1986). More recently, another turned up at Jones Beach State Park in New York in early October 2000. Two birds scarcely make a pattern of occurrence, of course. It is tempting to speculate, however, that if NJ ever gets another Cassin's Sparrow, a place like Sandy Hook would be as good as any for it to touch down.

Swinebroad, Jeff. 1966. Cassin's Sparrow in New Jersey. Auk 83:129. PDF here

Tufts, Robie W. 1986. Birds of Nova Scotia. Nimbus/Nova Scotia Museum, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Third edition.

Cassin's Sparrow is a very rare vagrant in the East; there are a few records for the Midwest. One bird made it all the way to Seal Island, Nova Scotia in 1974; that was a spring bird (Tufts 1986). More recently, another turned up at Jones Beach State Park in New York in early October 2000. Two birds scarcely make a pattern of occurrence, of course. It is tempting to speculate, however, that if NJ ever gets another Cassin's Sparrow, a place like Sandy Hook would be as good as any for it to touch down.

Swinebroad, Jeff. 1966. Cassin's Sparrow in New Jersey. Auk 83:129. PDF here

Tufts, Robie W. 1986. Birds of Nova Scotia. Nimbus/Nova Scotia Museum, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Third edition.

Labels:

"island beach",

"ocean county",

1961,

sparrow

Saturday, September 16, 2006

Black-capped Petrel

On this day in 1991, a pelagic trip to the Hudson Canyon found NJ's first Black-capped Petrel. NY also claims this bird, which may have been a result of the passage of Hurricane Bob. NY has the most records of this species for the local region, and most of those are also related to the passage of hurricanes (Levine 1998). One of Massachusetts' records was also during Bob, a bird off Eastham on Cape Cod (Veit & Petersen 1993). Black-capped Petrels regularly range northward in the Gulf Stream as far as North Carolina, so they are to be looked for on pelagic trips, whether or not hurricanes are involved.

NJ's only other record of Black-capped Petrel was a total of eight seen in off the Concrete Ship in Cape May during an afternoon seawatch after the passage of Hurricane Bertha on 13 July 1996 (NJ Hotline of 17 July 1996).

Levine, Emanuel. 1998. Bull's Birds of New York State. Comstock, Ithaca, NY.

Veit, Richard R., & Wayne R. Petersen. 1993. Birds of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Lincoln, MA.

NJ's only other record of Black-capped Petrel was a total of eight seen in off the Concrete Ship in Cape May during an afternoon seawatch after the passage of Hurricane Bertha on 13 July 1996 (NJ Hotline of 17 July 1996).

Levine, Emanuel. 1998. Bull's Birds of New York State. Comstock, Ithaca, NY.

Veit, Richard R., & Wayne R. Petersen. 1993. Birds of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Lincoln, MA.

Labels:

"hudson canyon",

1991,

hurricane,

pelagic,

petrel

Friday, September 15, 2006

Bell's Vireo

On this day in 1959, a Bell's Vireo was netted by Mr. and Mrs. Albert Schnitzler and subsequently collected by Joseph Jehl, Jr., at Island Beach State Park in Ocean County (Jehl 1960). That bird, an immature female, was found just ten days before another Bell's Vireo was caught and banded a little to the north at Tiana Beach near Shinnecock Inlet on Long Island, New York (Bull 1975). Prior to these records, the only other unequivocal Eastern record was a bird taken on 11 November 1897 in Durham, New Hampshire (Jehl 1960).

There was a gap between this first record and more recent ones, which started in 1994. All four of the recent records come that rarity vortex, Cape May. One of these birds occurred exactly 39 years to the day after the first state record, but the others have come later in fall. One appeared for a few days in October-November 1994; the other two stayed for a month from December into January (one in 1996-1997 and one in 2001-2002).

Bell's Vireo is one of the more uncommon western strays; New Jersey and New York have the most records in the region. There are a number of sight reports, but this species must be identified with care.

Bull, John. 1975. Birds of the New York Area. Dover, New York, NY.

Jehl, Joseph R., Jr. 1960. Bell's Vireo in New Jersey. Wilson Bulletin 72:404. PDF here

There was a gap between this first record and more recent ones, which started in 1994. All four of the recent records come that rarity vortex, Cape May. One of these birds occurred exactly 39 years to the day after the first state record, but the others have come later in fall. One appeared for a few days in October-November 1994; the other two stayed for a month from December into January (one in 1996-1997 and one in 2001-2002).

Bell's Vireo is one of the more uncommon western strays; New Jersey and New York have the most records in the region. There are a number of sight reports, but this species must be identified with care.

Bull, John. 1975. Birds of the New York Area. Dover, New York, NY.

Jehl, Joseph R., Jr. 1960. Bell's Vireo in New Jersey. Wilson Bulletin 72:404. PDF here

Labels:

"island beach",

"ocean county",

1959,

vireo

Thursday, September 14, 2006

Spotted Redshank

On this day in 1978, C. Clark and P. Fahey found a Spotted Redshank at Brigantine NWR. This bird remained until 28 September 1978, then moved on, but it returned the following year from 28 September to 8 October 1979. The only other record of Spotted Redshank in NJ is from 22-23 October 1993, also at Brig. The most notorious "Spotted Redshank" in NJ birding history, however, might be the 1973 Brig bird that turned out to be an oiled Greater Yellowlegs (Kaufman 1997, Smith 1974).

Mlodinow (1999) gives an extensive account of Spotted Redshank occurrence in North America. By far the most records come from the Aleutians, but eastern North America has quite a few as well. Mlodinow suggests that eastern Spotted Redshanks may come across the continent, ultimately originating in Asia.

This species' showy black alternate plumage is briefly held, so that birders hoping for a redshank in NJ are best advised to scrutinize yellowlegs carefully.

Kaufman, Kenn. 1997. Kingbird Highway. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, MA.

Mlodinow, Steven G. 1999. Spotted Redshank and Common Greenshank in North America. North American Birds 53:124-130.

Smith, P. William, Jr. 1974. Spotted Redshank Vs. Soiled Yellowlegs. Birding 6:84-86.

Mlodinow (1999) gives an extensive account of Spotted Redshank occurrence in North America. By far the most records come from the Aleutians, but eastern North America has quite a few as well. Mlodinow suggests that eastern Spotted Redshanks may come across the continent, ultimately originating in Asia.

This species' showy black alternate plumage is briefly held, so that birders hoping for a redshank in NJ are best advised to scrutinize yellowlegs carefully.

Kaufman, Kenn. 1997. Kingbird Highway. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, MA.

Mlodinow, Steven G. 1999. Spotted Redshank and Common Greenshank in North America. North American Birds 53:124-130.

Smith, P. William, Jr. 1974. Spotted Redshank Vs. Soiled Yellowlegs. Birding 6:84-86.

Labels:

"atlantic county",

1978,

brigantine,

shorebird

Long-billed Curlew

On this day in 1880, Dr. W. L. Abbott shot a Long-billed Curlew on Five Mile Beach in Cape May County. This barrier island currently hosts the Wildwoods.

Stone (1965) said the Cape May gunners called it the Sickle-bill. In Absecon, Pleasantville and Somers Point they called it Buzzard Curlew. The Pleasantville gunners also inclined towards naming it Smoker, Old Smoker or Lousy-bill; in Cape May Court House, it was Mowyer. Perhaps the Tuckerton gunners had a line in to the AOU when they called it Long-billed Curlew (Trumbull 1888).

In other words, Abbott's curlew may have been the first state record reviewed and accepted by the NJBRC (the specimen currently resides at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia), but it was not the true first state record. The Long-billed Curlew was one of the shorebirds that was favored by market gunners and, as a result, almost shot out of existence. The Eskimo Curlew was another casualty of this profession. Alexander Wilson wrote about the regular migrations of the species through NJ in mid-May and September; he wrote in 1812. By the time W. E. D. Scott visited Long Beach in April 1877, he considered it "very rare," not to mention "shy" (Stone 1965). I guess the prospect of gunplay might make anyone shy.

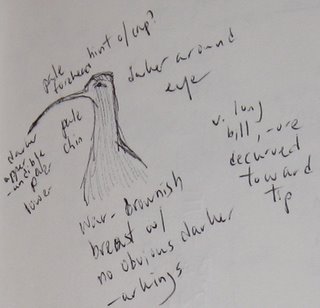

Almost 100 years passed between another record from Five Mile Beach in 1898 and a record from Cape May in 1987. In the late 1980s, I found birding. I developed a fascination with shorebirds, looked at field guides and thought seeing a Long-billed Curlew would be a really neat thing. I was sure I'd have to go out west to accomplish the feat, but I was wrong. My lifer Long-billed Curlew was the one that showed up in North Wildwood (a slice of bayside on Five Mile Beach) in 2002. As remarkable as this overwintering curlew was, more remarkable was its return the following year. Then there was the one that visited an airport in Whiting, in the Pine Barrens, during the day, then lit out toward Toms River in the evening. I saw that one too (the sketch that illustrates this post is of the North Wildwood curlew).

Neighboring states tell a similar story of the Long-billed Curlew; formerly abundant, then shot out by market gunners. Long Island seems to have been another favored location (Levine 1998). It still winters in the Southeast, but NJ's current birders have been very fortunate in the recent pulse of Long-billed Curlew records. May there be more to come.

Levine, Emanuel. 1998. Bull's Birds of New York State. Comstock, Ithaca, NY.

Stone, Witmer. 1965. Bird Studies at Old Cape May: An Ornithology of Coastal New Jersey. Dover, New York, NY.

Trumbull, Gurdon. 1888. Names and Portraits of Birds Which Interest Gunners. Harper & Brothers, New York, NY.

Labels:

"cape may county",

1880,

shorebird,

wildwood

Saturday, September 09, 2006

Lesser Black-backed Gull

On this day in 1934, Charles Urner and James L. Edwards found a Lesser Black-backed Gull at Beach Haven in Ocean County. Not only was this bird a first for NJ, it was the first North American record outside of Greenland (Edwards 1935, Post & Lewis 1995).

More records of this species accumulated, at first slowly but then more quickly, so that the Lesser Black-backed Gull is now a regular part of NJ's avifauna. Walsh et al. (1999) give a high count of 53 birds at Florence in Burlington County on 20 March 1997. Florence, of course, is just across the Delaware River from the massive Tullytown dump in Pennsylvania, a location that concentrates gulls. That high count has since been eclipsed on more than one occasion; the current state high count of Lesser Black-backed Gulls was made by Ward Dasey at Florence on 15 November 2003 and amounted to 214+ birds (Driver 2004). As numbers have increased, so have sightings of immature birds, and records can now be found throughout the year, even during the summer. It seems probable that this species must nest somewhere in North America, but there is still no hard proof. Sightings have increased across the country, but the East Coast is still this species' stronghold.

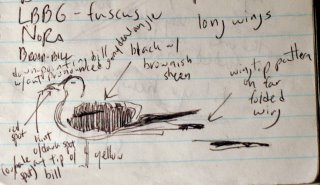

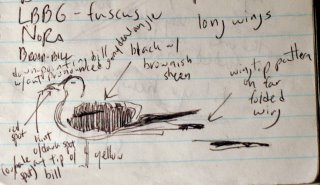

Walsh et al. state that southward-bound migrants occur "early in the fall, usually by mid-September." This fits perfectly with the date of the first record. Although graellsii of western Europe is the expected subspecies, Edwards' description of the first NJ bird states that the bird's back color appeared to be the same as that of Great Black-backed Gulls nearby; the observers circled the bird to make sure that the angle of the light was not affecting the bird's appearance. As a result, the observers thought that the subspecies involved was fuscus, which is native to northern Scandinavia. Adult birds of the subspecies intermedius, which occurs further south in Scandinavia, also have a black mantle, while adult graellsii birds have a slaty mantle that contrasts with black wingtips. Today's birders also have to consider the so-called "Dutch intergrades" between graellsii and intermedius when confronted by a Lesser Black-backed Gull with a darker-than-normal mantle (Post & Lewis 1995). Light conditions and the angle of the bird respective to the observer can also make dramatic differences in the apparent shade of a gull's mantle.

As anyone who has dabbled in gull identification knows, it is often a frustrating pursuit. However, I still find that a day with an elegant, long-winged Lesser Black-backed Gull on the list is a good day in the field.

(Illustrative disclaimer: these field notes were not taken in NJ. They were actually taken at the Kuusamo dump in Finland, and they attempt to depict an adult fuscus Lesser Black-back.)

Driver, Paul J. 2004. 2003 Fall Field Notes, Region 4. New Jersey Birds 30:15-18.

Edwards, James L. 1935. The Lesser Black-backed Gull in New Jersey. Auk 52:85. PDF here

Post, Peter W., & Robert H. Lewis. 1995. The Lesser Black-backed Gull in the Americas: Occurrence and Subspecific Identity. Birding 27:282-290; 370-380.

Walsh, Joan, Vince Elia, Rich Kane, & Thomas Halliwell. 1999. Birds of New Jersey. New Jersey Audubon Society, Bernardsville, NJ.

More records of this species accumulated, at first slowly but then more quickly, so that the Lesser Black-backed Gull is now a regular part of NJ's avifauna. Walsh et al. (1999) give a high count of 53 birds at Florence in Burlington County on 20 March 1997. Florence, of course, is just across the Delaware River from the massive Tullytown dump in Pennsylvania, a location that concentrates gulls. That high count has since been eclipsed on more than one occasion; the current state high count of Lesser Black-backed Gulls was made by Ward Dasey at Florence on 15 November 2003 and amounted to 214+ birds (Driver 2004). As numbers have increased, so have sightings of immature birds, and records can now be found throughout the year, even during the summer. It seems probable that this species must nest somewhere in North America, but there is still no hard proof. Sightings have increased across the country, but the East Coast is still this species' stronghold.

Walsh et al. state that southward-bound migrants occur "early in the fall, usually by mid-September." This fits perfectly with the date of the first record. Although graellsii of western Europe is the expected subspecies, Edwards' description of the first NJ bird states that the bird's back color appeared to be the same as that of Great Black-backed Gulls nearby; the observers circled the bird to make sure that the angle of the light was not affecting the bird's appearance. As a result, the observers thought that the subspecies involved was fuscus, which is native to northern Scandinavia. Adult birds of the subspecies intermedius, which occurs further south in Scandinavia, also have a black mantle, while adult graellsii birds have a slaty mantle that contrasts with black wingtips. Today's birders also have to consider the so-called "Dutch intergrades" between graellsii and intermedius when confronted by a Lesser Black-backed Gull with a darker-than-normal mantle (Post & Lewis 1995). Light conditions and the angle of the bird respective to the observer can also make dramatic differences in the apparent shade of a gull's mantle.

As anyone who has dabbled in gull identification knows, it is often a frustrating pursuit. However, I still find that a day with an elegant, long-winged Lesser Black-backed Gull on the list is a good day in the field.

(Illustrative disclaimer: these field notes were not taken in NJ. They were actually taken at the Kuusamo dump in Finland, and they attempt to depict an adult fuscus Lesser Black-back.)

Driver, Paul J. 2004. 2003 Fall Field Notes, Region 4. New Jersey Birds 30:15-18.

Edwards, James L. 1935. The Lesser Black-backed Gull in New Jersey. Auk 52:85. PDF here

Post, Peter W., & Robert H. Lewis. 1995. The Lesser Black-backed Gull in the Americas: Occurrence and Subspecific Identity. Birding 27:282-290; 370-380.

Walsh, Joan, Vince Elia, Rich Kane, & Thomas Halliwell. 1999. Birds of New Jersey. New Jersey Audubon Society, Bernardsville, NJ.

Labels:

"beach haven",

"ocean county",

1934,

gull

Friday, September 08, 2006

Brown Noddy

On this day in 1979, NJ got its first (and so far only) record of Brown Noddy. The bird was seen in Cape May by Pete Dunne, Dave Ward, R. Gardner and others in the wake of Hurricane David. Other David birds included nine records of Sooty Terns on 6 September 1979 (stretching from Cape May to Wyckoff in Bergen County) and a Bridled Tern in Cape May on 7 September 1979.

Labels:

"cape may county",

"cape may",

1979,

hurricane,

noddy,

tern

Thursday, September 07, 2006

Eurasian Collared-Dove

On this day in 1997, Paul Lehman found a Eurasian Collared-Dove perched on top of a utility pole on Alexander Ave. in Cape May Point. Although word went out immediately, the bird had departed by the time the first chaser arrived ten minutes later (Lehman 1998). The bird could not be relocated.

The Eurasian Collared-Dove made an explosive colonization of Europe in the last century and now looks poised to add North America to its portfolio. The original source of the North American population is unclear, and the issue is muddied by birds that have escaped or been released from captivity (Romagosa and McEneaney 1999). What is apparent is that NJ birders need to be prepared for more records of these doves. At this writing, there are five accepted records for NJ: four from Cape May and one from Sandy Hook (Barnes et al. in litt.). There are two records each for May and September, and one for July.

Since doves may give only fleeting views, it's crucial for birders to concentrate on details of the wing pattern and undertail pattern to clinch this identification. Hybrids with Ringed Turtle-Dove need to be ruled out. Knowing the distinctive call of this dove may help, too.

When House Sparrows and European Starlings arrived in this country, many bird students of the day found them beneath notice because of their captive origins. As a result, we have a spotty record of the nature of their expansion across the continent. Hopefully we will not make the same mistake when it comes to tracking the Eurasian Collared-Dove.

Barnes, Scott, Joe Burgiel, Vince Elia, Jennifer Hanson, & Laurie Larson. In litt. New Jersey Bird Records Committee: Annual Report 2006. New Jersey Birds Fall 2006 issue.

Lehman, Paul. 1998. A Eurasian Collared-Dove at Cape May: First Sighting in New Jersey. Records of New Jersey Birds 24:5-6.

Romagosa, Christina M., & Terry McEneaney. 1999. Eurasian Collared-Dove in North America and the Caribbean. North American Birds 53:348-353.

The Eurasian Collared-Dove made an explosive colonization of Europe in the last century and now looks poised to add North America to its portfolio. The original source of the North American population is unclear, and the issue is muddied by birds that have escaped or been released from captivity (Romagosa and McEneaney 1999). What is apparent is that NJ birders need to be prepared for more records of these doves. At this writing, there are five accepted records for NJ: four from Cape May and one from Sandy Hook (Barnes et al. in litt.). There are two records each for May and September, and one for July.

Since doves may give only fleeting views, it's crucial for birders to concentrate on details of the wing pattern and undertail pattern to clinch this identification. Hybrids with Ringed Turtle-Dove need to be ruled out. Knowing the distinctive call of this dove may help, too.

When House Sparrows and European Starlings arrived in this country, many bird students of the day found them beneath notice because of their captive origins. As a result, we have a spotty record of the nature of their expansion across the continent. Hopefully we will not make the same mistake when it comes to tracking the Eurasian Collared-Dove.

Barnes, Scott, Joe Burgiel, Vince Elia, Jennifer Hanson, & Laurie Larson. In litt. New Jersey Bird Records Committee: Annual Report 2006. New Jersey Birds Fall 2006 issue.

Lehman, Paul. 1998. A Eurasian Collared-Dove at Cape May: First Sighting in New Jersey. Records of New Jersey Birds 24:5-6.

Romagosa, Christina M., & Terry McEneaney. 1999. Eurasian Collared-Dove in North America and the Caribbean. North American Birds 53:348-353.

Labels:

"cape may county",

"cape may",

1997,

dove

Juvenile Curlew Sandpiper

On this day in 1997, a juvenile Curlew Sandpiper was identified by Bob Confer in a farm field near the Clarksville Sod Farm in Burlington County. Although the bird was present for a few days before this (Dasey 1997), looks sufficient for identification only came on the 7th. Ed Bruder was the original finder of this bird. The bird remained for one more day, 8 September, then departed.

This individual went on to become the first fully accepted record of the species for NJ. Although the state has many previous reports, the NJBRC elected to review only post-1996 reports of this species due to the difficulty of unearthing adequate documentation on so many reports after the fact (Halliwell et al. 2000). John James Audubon himself reported shooting two Curlew Sandpipers in spring 1829 at Great Egg Harbor in Atlantic County (Stone 1965); this is the first known report for North America.

The Curlew Sandpiper might be thought of as a "regular rarity" in NJ; most years have at least one report of the species. Most reports come from May with a secondary peak in July (Hanson 1999). In contrast to many vagrant species, most reports are of adults rather than immatures, a pattern that holds across the Northeast. It remains uncertain whether juvenile Curlew Sandpipers are overlooked because their plumage is far subtler than that of an adult in even partial alternate plumage, or whether there is a real difference in distribution of these age classes. A fuller discussion of Curlew Sandpiper distribution can be found in Hanson (1999). In any case, the Burlington County bird is noteworthy for its age, since there are no other known reports of juvenile Curlew Sandpipers for the state.

The Burlington County location is also noteworthy. Curlew Sandpipers are known for their site loyalty; Brigantine NWR in Atlantic County is probably the classic example of a location traditionally favored by the species. Part of this site loyalty may stem from adult birds repeating a migration path throughout their lifetimes, but there is no hard information on this. Most of the favored locations have been coastal ones. On the other hand, the appearance of such species as Pacific Golden-Plover and Sharp-tailed Sandpiper on inland sod farms demonstrates that rare shorebirds can show up in non-coastal locations.

Dasey, Ward W. 1997. 1996 Fall field notes, Region 4. Records of New Jersey Birds 22:14-16.

Halliwell, Tom, Rich Kane, Laurie Larson, & Paul Lehman. 2000. The Historical Report of the New Jersey Bird Records Committee: Rare Bird Reports Through 1989. Records of New Jersey Birds 26:13-44.

Hanson, Jennifer W. 1999. Curlew Sandpipers (Calidris ferruginea) in New Jersey. Records of New Jersey Birds 25:26-31.

Stone, Witmer. Bird Studies at Old Cape May: An Ornithology of Coastal New Jersey. Dover, New York, NY.

This individual went on to become the first fully accepted record of the species for NJ. Although the state has many previous reports, the NJBRC elected to review only post-1996 reports of this species due to the difficulty of unearthing adequate documentation on so many reports after the fact (Halliwell et al. 2000). John James Audubon himself reported shooting two Curlew Sandpipers in spring 1829 at Great Egg Harbor in Atlantic County (Stone 1965); this is the first known report for North America.

The Curlew Sandpiper might be thought of as a "regular rarity" in NJ; most years have at least one report of the species. Most reports come from May with a secondary peak in July (Hanson 1999). In contrast to many vagrant species, most reports are of adults rather than immatures, a pattern that holds across the Northeast. It remains uncertain whether juvenile Curlew Sandpipers are overlooked because their plumage is far subtler than that of an adult in even partial alternate plumage, or whether there is a real difference in distribution of these age classes. A fuller discussion of Curlew Sandpiper distribution can be found in Hanson (1999). In any case, the Burlington County bird is noteworthy for its age, since there are no other known reports of juvenile Curlew Sandpipers for the state.

The Burlington County location is also noteworthy. Curlew Sandpipers are known for their site loyalty; Brigantine NWR in Atlantic County is probably the classic example of a location traditionally favored by the species. Part of this site loyalty may stem from adult birds repeating a migration path throughout their lifetimes, but there is no hard information on this. Most of the favored locations have been coastal ones. On the other hand, the appearance of such species as Pacific Golden-Plover and Sharp-tailed Sandpiper on inland sod farms demonstrates that rare shorebirds can show up in non-coastal locations.

Dasey, Ward W. 1997. 1996 Fall field notes, Region 4. Records of New Jersey Birds 22:14-16.

Halliwell, Tom, Rich Kane, Laurie Larson, & Paul Lehman. 2000. The Historical Report of the New Jersey Bird Records Committee: Rare Bird Reports Through 1989. Records of New Jersey Birds 26:13-44.

Hanson, Jennifer W. 1999. Curlew Sandpipers (Calidris ferruginea) in New Jersey. Records of New Jersey Birds 25:26-31.

Stone, Witmer. Bird Studies at Old Cape May: An Ornithology of Coastal New Jersey. Dover, New York, NY.

Labels:

"burlington county",

"sod farm",

1997,

shorebird

Tuesday, September 05, 2006

75 Black Terns on the Delaware

On this day in 1907, Richard C. Harlow and Richard F. Miller found about 75 Black Terns on the Delaware River behind Petty's Island at Camden. They took six specimens and all proved to be immatures. Miller stated that all the birds they saw were juveniles, but since immature plumage and adult nonbreeding plumage are similar in this species, it is possible that there were some adults mixed in. These were the days of shotgun ornithology.

On 10 September 1907, Harlow and Miller saw 50 Black Terns in this location and at Philadelphia; on that occasion, eight specimens were taken. Again, all the birds that were shot were immatures. The specimens were kept by Harlow and Miller for their collections, except for two that were given to Witmer Stone for his collection. Miller concluded by saying, "The Terns were undoubtedly a migrating flock driven inland by a recent storm." Reference to 1907 hurricane data here does not show any hurricanes near the time of these sightings, so it must have been a different kind of storm system. One also wonders whether the terns were "driven inland," or just grounded by the storm.

This observation may gain extra interest because of the recent fallout of Black Terns across NJ. Most concentrations of migrating Black Terns are found on the coast; the unusual aspect of the recent Black Tern fallout is the fact that terns were found in such locations as Spruce Run Reservoir in Hunterdon County and Assunpink WMA in inland Monmouth County. Walsh et al's Birds of New Jersey gives a high count of 50 individuals found at Hancock's Bridge in Salem County on 14 August 1994. As Dasey says in his 1994 fall season report in Records of New Jersey Birds, "Aug. 14 brought the heaviest Black Tern movement to hit the region in many years...Subsequently, it was shown the movement was widespread, stretching from the NJ coast into at least central Pennsylvania." He also mentions 9 individuals at the mouth of Pennsauken Creek at Palmyra and 5 more at Mannington, but does not link the terns with a particular weather pattern.

However, on the same day, 65 Black Terns were seen at Donegal Lake in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, "after a heavy afternoon thunderstorm," according to McWilliams and Brauning's The Birds of Pennsylvania. The "coincidence" of large flocks of Black Terns being seen on the same day in places as widely separated as Salem County, NJ, and Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, starts to raise even more questions. Did weather conditions concentrate the terns in an unusual way? Or was it just a good year for Black Tern production, leading to more birds coming south, which might then be grounded by localized weather systems? Without a deeper search into the local ornithological literature and archives of weather records, these questions will probably remain unanswered. It sounds like a worthy research project, however.

Dasey, Ward W. 1994-5. 1994 Fall field notes, Region 4. Records of New Jersey Birds 20:97-99.

McWilliams, Gerald M., & Daniel W. Brauning. 2000. The Birds of Pennsylvania. Comstock, Ithaca, NY.

Miller, Richard F. 1908. The Black Tern at Camden, N.J., and Philadelphia, Pa. Auk 25:215-216. PDF here

Walsh, Joan, Vince Elia, Rich Kane, & Thomas Halliwell. 1999. Birds of New Jersey. New Jersey Audubon Society, Bernardsville, NJ.

On 10 September 1907, Harlow and Miller saw 50 Black Terns in this location and at Philadelphia; on that occasion, eight specimens were taken. Again, all the birds that were shot were immatures. The specimens were kept by Harlow and Miller for their collections, except for two that were given to Witmer Stone for his collection. Miller concluded by saying, "The Terns were undoubtedly a migrating flock driven inland by a recent storm." Reference to 1907 hurricane data here does not show any hurricanes near the time of these sightings, so it must have been a different kind of storm system. One also wonders whether the terns were "driven inland," or just grounded by the storm.

This observation may gain extra interest because of the recent fallout of Black Terns across NJ. Most concentrations of migrating Black Terns are found on the coast; the unusual aspect of the recent Black Tern fallout is the fact that terns were found in such locations as Spruce Run Reservoir in Hunterdon County and Assunpink WMA in inland Monmouth County. Walsh et al's Birds of New Jersey gives a high count of 50 individuals found at Hancock's Bridge in Salem County on 14 August 1994. As Dasey says in his 1994 fall season report in Records of New Jersey Birds, "Aug. 14 brought the heaviest Black Tern movement to hit the region in many years...Subsequently, it was shown the movement was widespread, stretching from the NJ coast into at least central Pennsylvania." He also mentions 9 individuals at the mouth of Pennsauken Creek at Palmyra and 5 more at Mannington, but does not link the terns with a particular weather pattern.

However, on the same day, 65 Black Terns were seen at Donegal Lake in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, "after a heavy afternoon thunderstorm," according to McWilliams and Brauning's The Birds of Pennsylvania. The "coincidence" of large flocks of Black Terns being seen on the same day in places as widely separated as Salem County, NJ, and Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, starts to raise even more questions. Did weather conditions concentrate the terns in an unusual way? Or was it just a good year for Black Tern production, leading to more birds coming south, which might then be grounded by localized weather systems? Without a deeper search into the local ornithological literature and archives of weather records, these questions will probably remain unanswered. It sounds like a worthy research project, however.

Dasey, Ward W. 1994-5. 1994 Fall field notes, Region 4. Records of New Jersey Birds 20:97-99.

McWilliams, Gerald M., & Daniel W. Brauning. 2000. The Birds of Pennsylvania. Comstock, Ithaca, NY.

Miller, Richard F. 1908. The Black Tern at Camden, N.J., and Philadelphia, Pa. Auk 25:215-216. PDF here

Walsh, Joan, Vince Elia, Rich Kane, & Thomas Halliwell. 1999. Birds of New Jersey. New Jersey Audubon Society, Bernardsville, NJ.

Labels:

"camden county",

"petty's island",

1907,

camden,

tern

Monday, September 04, 2006

Pacific Golden-Plover

On this day in 2001, Richard Crossley found a Pacific Golden-Plover at Johnson Sod Farm on the border of Salem and Cumberland Counties. The bird stayed through 16 September 2001 and was seen by many. This is the only NJ state record of the species so far, and one of very few East Coast records. The following spring, a Pacific Golden-Plover was found at Plum Island in Massachusetts on 21 April 2002; that bird remained until 5 May 2002. There's also an old Maine specimen record from 11 September 1911.

Finding a Pacific Golden-Plover in a flock of American Golden-Plovers will always be a difficult task, but it's possible that other Pacifics have been overlooked because of the identification issues. Also, the two species were considered to be one (Lesser Golden-Plover) until relatively recently, so this doubtless helped it fly under many birders' radar. Interestingly, a bird that may be Utah's first record of the species is currently being discussed on the ID-Frontiers listserv, so now is clearly the time to be alert for this species.

The first state record article, "New Jersey's First Pacific-Golden Plover" by Richard Crossley, was published in the Fall 2002 issue of Records of New Jersey Birds, pages 57-60. Other references include Angus Wilson's discussion on the bird, which he posted on his Ocean Wanderers website.

Finding a Pacific Golden-Plover in a flock of American Golden-Plovers will always be a difficult task, but it's possible that other Pacifics have been overlooked because of the identification issues. Also, the two species were considered to be one (Lesser Golden-Plover) until relatively recently, so this doubtless helped it fly under many birders' radar. Interestingly, a bird that may be Utah's first record of the species is currently being discussed on the ID-Frontiers listserv, so now is clearly the time to be alert for this species.

The first state record article, "New Jersey's First Pacific-Golden Plover" by Richard Crossley, was published in the Fall 2002 issue of Records of New Jersey Birds, pages 57-60. Other references include Angus Wilson's discussion on the bird, which he posted on his Ocean Wanderers website.

A Sunday note from Salem County

Yesterday while tooling around the southwest corner of the state, we stumbled upon a farm field near Woodstown with at least 65 Cattle Egrets in it. This is a far cry from the state high count quoted in Walsh et al's Birds of New Jersey, but it's the most that we've seen for a long time. Birds of New Jersey states that Cattle Egrets hit their peak of abundance at this time of year due to post-breeding dispersal. These particular birds probably came over from the colony on Pea Patch Island, in Delaware.

For the record, the state high count was made on 31 August 1987 at Mannington Marsh; that was a cool 2,000 birds.

For the record, the state high count was made on 31 August 1987 at Mannington Marsh; that was a cool 2,000 birds.

Labels:

"salem county",

egret,

heron,

woodstown

Friday, September 01, 2006

Witmer Stone goes for a stroll

On this day in 1920, Witmer Stone walked from Cape May to Cape May Point and wound up with a list of 86 species. He didn't give any further details on his "big morning" when he mentioned it in Bird Studies at Old Cape May, unfortunately. Elsewhere in the same work, Stone gave cumulative month lists for Cape May; September's total was 213, so he saw 40 percent of that total on his morning walk.

I think it's appropriate to start this blog with a moment in the life of Witmer Stone. Today we think of him as the authority who published three noteworthy books on NJ's avifauna; one of them, the aforementioned Bird Studies, may be one of the greatest bird books of all time. He was also a pivotal figure in the history of the Delaware Valley Ornithological Society (DVOC); James A. G. Rehn called Stone, "the most outstanding figure in [the DVOC's] history" in the obituary that he penned for Cassinia. This obituary was reprinted as part of the front matter in Dover's reissue of Bird Studies in Old Cape May and does a better job than I ever could of stating Stone's background and accomplishments. You can find a PDF of an expanded version of it that was printed in the Auk on SORA (Searchable Ornithological Research Archive).

One thing that Stone devoted much time to was the compilation of bibliographies. The Birds of New Jersey, Their Nests and Eggs has an extensive bibliography; this was Stone's best attempt to compile an all-inclusive list of sources for NJ ornithology. Later issues of Cassinia followed the tradition with updates containing the most recent publications on the state's birdlife. I suspect this love of bibliography came from the example of Stone's father Frederick, who was a historian and Librarian of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Of course, the eminent ornithologist Elliott Coues was also badly bitten by the bibliographic bug, so Stone was hardly the first bird student to fall prey to this malady.

Bibliography, in the end, is about looking back the way we've come, and Stone put this historical impulse to good use, particularly in his Cape May magnum opus. We would know far less about NJ's birdlife if he hadn't looked back from his own time. This is the heritage of all NJ birders. All of us depend on the vast body of records and reports that were accumulated, published and compiled by others. We are lucky to bird in a state with such a long ornithological history; much of the knowledge we take for granted, that we pick up by osmosis as we learn to bird, was discovered by others. That's what this blog is all about.

Returning to Stone's morning walk, I wondered if I could compare it to modern birding, numbers-wise. ABA's 2005 Big Day Report gives a NJ September Big Day record of 144, but of course this isn't for Cape May exclusively; ABA doesn't keep county listing milestones (alas). I pulled out David Sibley's The Birds of Cape May but realized that Sibley treats the entire county, while Stone's area was confined to Cape Island and the oceanfront up as far as Avalon. Time is on our side as well; the longer you wait for certain vagrants to show up, the better the probability they will (never mind birds like Cattle Egret which were unknown in the state when Stone wrote). So an exact comparison is not to be had. On the other hand, comparing Stone's month lists and Sibley's bar graphs is a very instructive exercise that I recommend to anyone who has access to both books.

I think it's appropriate to start this blog with a moment in the life of Witmer Stone. Today we think of him as the authority who published three noteworthy books on NJ's avifauna; one of them, the aforementioned Bird Studies, may be one of the greatest bird books of all time. He was also a pivotal figure in the history of the Delaware Valley Ornithological Society (DVOC); James A. G. Rehn called Stone, "the most outstanding figure in [the DVOC's] history" in the obituary that he penned for Cassinia. This obituary was reprinted as part of the front matter in Dover's reissue of Bird Studies in Old Cape May and does a better job than I ever could of stating Stone's background and accomplishments. You can find a PDF of an expanded version of it that was printed in the Auk on SORA (Searchable Ornithological Research Archive).

One thing that Stone devoted much time to was the compilation of bibliographies. The Birds of New Jersey, Their Nests and Eggs has an extensive bibliography; this was Stone's best attempt to compile an all-inclusive list of sources for NJ ornithology. Later issues of Cassinia followed the tradition with updates containing the most recent publications on the state's birdlife. I suspect this love of bibliography came from the example of Stone's father Frederick, who was a historian and Librarian of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Of course, the eminent ornithologist Elliott Coues was also badly bitten by the bibliographic bug, so Stone was hardly the first bird student to fall prey to this malady.

Bibliography, in the end, is about looking back the way we've come, and Stone put this historical impulse to good use, particularly in his Cape May magnum opus. We would know far less about NJ's birdlife if he hadn't looked back from his own time. This is the heritage of all NJ birders. All of us depend on the vast body of records and reports that were accumulated, published and compiled by others. We are lucky to bird in a state with such a long ornithological history; much of the knowledge we take for granted, that we pick up by osmosis as we learn to bird, was discovered by others. That's what this blog is all about.

Returning to Stone's morning walk, I wondered if I could compare it to modern birding, numbers-wise. ABA's 2005 Big Day Report gives a NJ September Big Day record of 144, but of course this isn't for Cape May exclusively; ABA doesn't keep county listing milestones (alas). I pulled out David Sibley's The Birds of Cape May but realized that Sibley treats the entire county, while Stone's area was confined to Cape Island and the oceanfront up as far as Avalon. Time is on our side as well; the longer you wait for certain vagrants to show up, the better the probability they will (never mind birds like Cattle Egret which were unknown in the state when Stone wrote). So an exact comparison is not to be had. On the other hand, comparing Stone's month lists and Sibley's bar graphs is a very instructive exercise that I recommend to anyone who has access to both books.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)